PHY.K02UF Molecular and Solid State Physics

|

| ||||

PHY.K02UF Molecular and Solid State Physics | ||||

The program that calculates the chemical potential using the charge neutrality condition from the previous page was put in a loop to calculate the chemical potential as a function of temperature. The black line in the plot below is the chemical potential. At low temperatures, the chemical potential is between the occupied states and the empty states. If there are more acceptors than donors, the chemical potential at low temperatures is below the empty acceptor energies (the light blue line). It then rises towards the middle of the band gap, where it remains for high temperatures. At high temperatures, there are so many electrons excited across the band gap that the concentration of electrons is approximately the same as the concentration of holes, and the situation aproaches that of an undoped semiconductor at high temperature. If there are more donors than acceptors, the chemical potential at low temperatures is above the occupied donor energies (the pink line) and falls to the middle of the band gap as the temperature increases. Try changing the ratio of $N_d$ to $N_a$ to see this effect. Notice that the size of the band gap typically decreases as the temperature increases.

| |||||||||

|

|

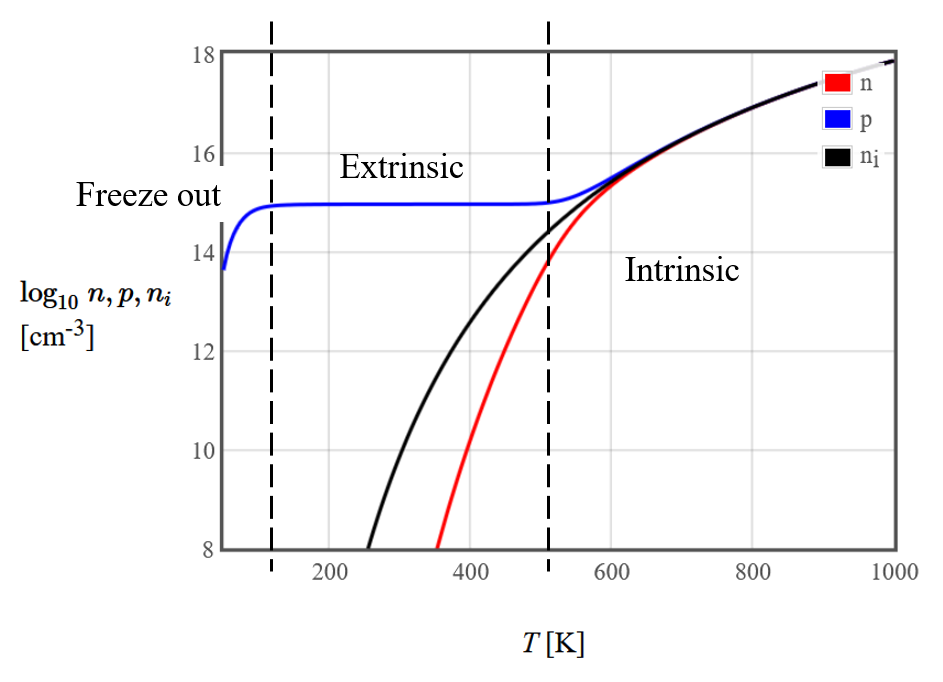

Once the chemical potential is known, the carrier concentrations $n$, $p$, and $n_i$ can be calculated from the formulas, $n=\frac{\sqrt{\pi}D_c}{2}(k_BT)^{3/2}\exp{\left(\frac{\mu-E_c}{k_BT}\right)}$, $p = \frac{\sqrt{\pi}D_v}{2}(k_BT)^{3/2}\exp\left(\frac{E_v-\mu}{k_BT}\right)$, and $n_i \approx \frac{\sqrt{\pi D_cD_v}}{2}(k_BT)^{3/2}\exp\left(\frac{-E_g}{2k_BT}\right)$. The carrier concentrations are plotted once against temperature $T$ and once against $1/T$. This is the same information plotted two ways. The motivation for plotting the carrier densities vs. $1/T$ is that $n_i$ is nearly a straight line when plotted this way.

In the carrier density plots, three regimes can be identified. There is a low-temperature regime where the electrons return to the donors from the conduction band, and the electrons return to the valence band from the acceptors. This is called the freeze-out regime, where there is a rapid decrease in the mobile charge carriers. Then there is a temperature regime where the majority charge carrier concentration remains about constant. This is called the extrinsic regime. At high temperatures, there are so many electrons that get excited across the band gap that the carrier concentrations $n$ and $p$ are greater than the doping concentration. This is called the intrinsic regime.

Most semiconductor devices are operated in the extrinsic regime. Below is a table of the properties of semiconductors in this regime.

n-type $N_d \gt N_a$ $$n\approx N_d -N_a$$ $$p \approx \frac{n_i^2}{n}$$ $$\qquad\mu \approx E_c+k_BT\ln\left(\frac{2n}{\sqrt{\pi}D_c(k_BT)^{3/2}}\right)\qquad$$ $$u \approx u_0 + \frac{3nk_BT}{2}$$ $$c_v \approx \frac{3nk_B}{2}$$ |

p-type $N_d \lt N_a$ $$p\approx N_a -N_d$$ $$n \approx \frac{n_i^2}{p}$$ $$\qquad\mu \approx E_v-k_BT\ln\left(\frac{2p}{\sqrt{\pi}D_c(k_BT)^{3/2}}\right)\qquad$$ $$u \approx u_0 + \frac{3pk_BT}{2}$$ $$c_v \approx \frac{3pk_B}{2}$$ |

Derivation for an $n$-type extrinsic semiconductor

In the extrinsic regime, the electrons and holes have properties similar to those of a classical ideal gas. In an ideal gas and the extrinsic regime, there are a constant number of noninteracting particles whose their kinetic energies is given by the equipartion theorem, $\frac{1}{2}mv^2 = \frac{1}{2}k_BT$. The average velocity of the charge carriers is the thermal velocity $v = \sqrt{k_BT/m}$. The specific heat of a classical ideal gas in this case is a constant, $c_v = \frac{3}{2}nk_B$. This contrasts with intrinsic semiconductors, where the number of particles is not held constant; $n_i$ increases rapidly with temperature, and the electron component of the specific heat contains a factor $\exp(-E_g/(k_BT))$ that goes quickly to zero as $T\rightarrow 0$. An early theory of metals by Drude also assumed that the velocity of electrons in metals was the thermal velocity. However, the average velocity of electrons in a metal is the Fermi velocity $v_F = \hbar k_F/m$, which is typically much higher than the thermal velocity. The electron component of the specific heat of a metal is typically proportional to temperature.

See www.ioffe.rssi.ru/SVA/NSM/Semicond/index.html for the bandgaps and donor and acceptor energies of various semiconductors.