PHY.K02UF Molecular and Solid State Physics

|

| ||||

PHY.K02UF Molecular and Solid State Physics | ||||

An electron in a constant magnetic field will travel in a circle in the plane perpendicular to the magnetic field, with angular frequency $\omega = \frac{eB_z}{m_e}$. If the magnetic field is oriented in the $z-$direction and there is also a constant electric field present, the trajectory of the electron, projected into the plane perpendicular to the magnetic field, will be a prolate cycloid as is illustrated below. The equations for the motion of a charged particle in constant electric and magnetic fields are shown to the right of the simulation.

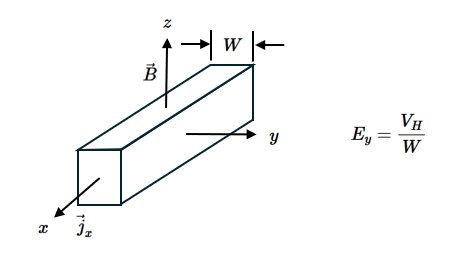

If the electric field is perpendicular to the magnetic field, the average motion of the electrons is perpendicular to both the electric field and the magnetic field. If the electrons experience collisions, the velocity of an electron is randomized after each collision, and it follows a prolate cycloid trajectory between the collisions. This results in an average current density that makes an angle, called the Hall angle $\theta_H$, with the electric field. In a typical experiment, a current is driven in the $x-$direction through a conductor while there is a magnetic field in the $z-$direction.

The Lorentz force will push the electrons in the $y-$direction $\vec{F} = q\vec{v}\times\vec{B} = -\frac{j_xB_z}{n}\hat{y}$. However, charge cannot flow out of the conductor in the $y-$direction, so an electric field is established to make the force in the $y-$direction zero, $E_y = -\frac{j_xB_z}{ne}$. This is often written as,

$$E_y = R_Hj_xB_z$$where $R_H$ is called the Hall constant and in the simple theory, $R_H = -\frac{1}{ne}$. The electric field is the Hall voltage $V_H$ measured across the conductor in the $y-$direction divided by the width $W$ of the conductor in the $y-$direction. The Hall angle can be determined by taking the ratio of the two components of the electric field, $E_x = \frac{j_x}{ne\mu}$ and $E_y = -\frac{j_xB_z}{ne}$ $$\tan\theta_H = \frac{E_y}{E_x}=-\mu B_z.$$

As $j_x$, $V_H$, and $B_z$ are experimentally accessible, the Hall effect is often used to determine the electron density $n$ of a conductor. However, the interpretation of the Hall coefficient is not always simple because it is sometimes positive and sometimes negative. A positive Hall coefficient indicates that the electronic transport is dominated by holes, and a negative Hall coefficient indicates that the electronic transport is dominated by electrons. In metals, a band structure calculation can be used to determine the Fermi surface. The curvature of the Fermi surface determines if the charge carriers are electrons or holes. If the Fermi surface exists in more than one Brillouin zone, both electrons and holes can be present.

An intrinsic semiconductor has an equal number of electrons and holes, but by doping a semiconductor, the chemical potential is shifted towards the conduction band or towards the valence band. If the chemical potential is close to the conduction band, the charge carriers will be electrons, and if it close to the valence band, the charge carriers will be holes.

Semiconductors with a low electron densities are used in Hall sensors which measure the magnetic field. A low electron density results in a large Hall voltage.